Lost Wisdom: How Contemporary Psychologists Lack Depth

A Hypothesis on the Decline of Scientific Thinking

I propose a hypothesis concerning the new generation of social scientists. I call it - The Google Scholar Search Problem.

Today's information landscape is drastically different, with a wealth of data available at our fingertips. This shift has made every published psychological article accessible with a few aptly chosen keywords. However, this reliance on Google within the field of psychology could be an intellectual crutch. I suspect that the abundance of readily available information might be diminishing psychologists' critical thinking skills and wisdom. Let's delve into why this might be the case.

Dependency on Immediate Answers

In the 1990’s, psychologists were torn. They couldn’t decide if curiosity was a feeling of pure joy, as Dr. Charles Spielberger suggested, or a restless, itch-you-need-to-scratch feeling, as argued by Dr. George Loewenstein. Most of us picture a curious person as joyously exploring. But when we realize we don't know something important, joy isn't the first thing we feel. Instead, we're driven to find answers, to ease the tension of not knowing. These are just two of the five known dimensions of curiosity, dubbed Joyous Exploration and Deprivation Sensitivity.

In today's world of Google Scholar, an empty search box waits for us to fill it with our thirst for knowledge. A parent recently wanted my opinion on a Mirtazapine prescription from a psychiatrist. I needed to catch up on the best depression treatments. So, I searched for large studies comparing various treatments. I typed "mirtazapine meta analysis." The second listed article was a robust analysis of 19,364 clients. The evidence suggested that this drug works well at low doses and is easy to tolerate. Ten minutes of searching/reading and I had an immediate answer for her vexing problem.

Solving a problem often leads us down a path of easy explanations. But, let's admit, that's a bit dull. It's like eating unagi every day. As scientists, we don't grow wiser by sticking to what's familiar. Our research suggests that wisdom and curiosity are best friends, joined at the hip by the thrill of exploration. In this digital age, it's tempting to gobble up quick answers. But where's the fun in that? Let's dive deeper. Let's explore.

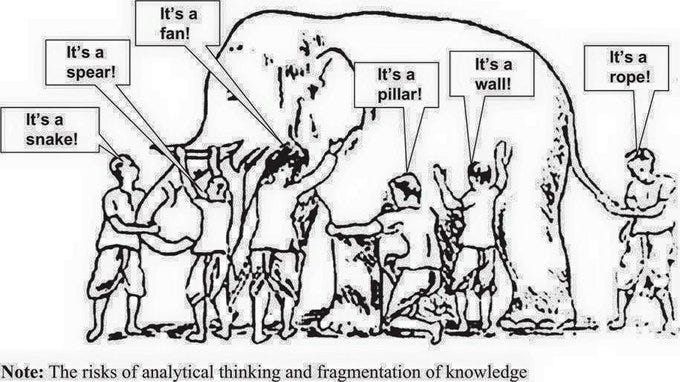

Information Glut and Superficial Knowledge

The internet is like a candy store for psychologists, brimming with research papers, articles, opinions, and books. But too much candy can lead to a sugar rush of confusion. It can be a real challenge to:

Spot the nuggets of reliable knowledge among the pebbles.

Untangle what we want to believe from what is actually true.

Put on our detective hats to critically evaluate the quality of the information we stumble upon.

This information glut can leave us with a patchwork quilt of knowledge, where understanding is as shallow as a kiddie pool and fiercely guarded. But remember, hoarding information doesn't equate to deep understanding or comprehensive analysis.

We need scientists who kick off with burning questions.

We need scientists who juggle multiple hypotheses like circus performers.

We need scientists who strive to take off their ideological glasses when testing ideas.

Undermining the Art of Inquiry and Discovery

Be wary of anyone beginning a sentence with…in my day. It is the origin of age stratified battles.

Which generation is the greatest.

Which generation is the smartest.

Which generation has the best musical taste.

(You know you want to know or at least argue about generational comparisons, which is why this topic is fodder for bestselling books.)

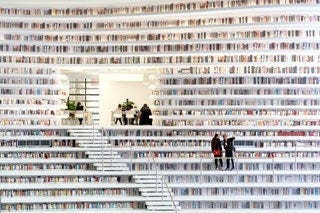

That said, in my day of being trained as a scientist, we didn’t use personalized filtering to uncover search results. We walked into a physical library and brought a stack of journals onto a desk and sifted through an issue’s table of contents. Or you went into an online database for a specific journal and sifted through the table of contents, scanning titles. With a comprehensive body of knowledge nearby, you experienced serendipity.

While searching through issues of Behaviour Research and Therapy for articles related to my dissertation topic - whether the experience of social anxiety interferes with group treatment for depression1 - I stumbled upon an article that would change the direction of my work. An article that I would never have actively searched for. Upon pursuing articles on the comorbidity of social anxiety and depression in treatment seeking individuals, I discovered how anxiety about feeling anxious “scars” certain individuals, which in turn, led me to ponder a new concept called psychological flexibility - and how to measure it better.

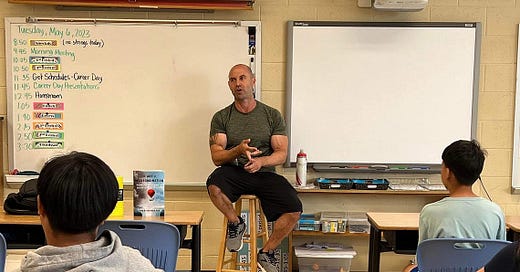

When I volunteered for Union Mill Elementary School’s career day (where my youngest attends), a kid asked, “where do your ideas for science and books come from?”

I explained the importance of diverse inputs.

Regularly put yourself in a position to find interesting things, people, and ideas.

Be sure to explore widely, beyond what you want to know toward what could be known.

Collect perspectives unlike your own and unlock them with a great deal of questioning and deep listening.

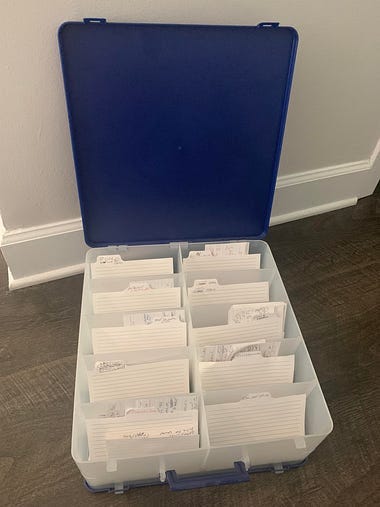

Store inputs in a way is easy to do. Consider a daily journal (I log my 3 extraordinary moments every day). Use index cards, tracking interesting sentences, stories, discoveries, and perspectives.

Every evolution and revolution has unforeseen consequences. The impact of rapid, voluminous access to information warrants careful consideration on how it impedes the cognitive abilities of scientists. A reliance on immediate answers, confirmation bias, information overload, and the erosion of curiosity all contribute to the decline of wisdom in individuals. It is crucial to recognize these pitfalls and actively reverse them. It is always the right time for more people to acquire wisdom. Which means doing whatever is possible to subvert barriers to wisdom attainment.

Leave a comment and help others by detailing your own wisdom building strategies. If you enjoyed this, please spread the word! Or click the heart button (always appreciated). Don’t be shy, leave suggestions, constructive criticisms, and dare I say, a few positive words about what resonated. Leave comments here or on LinkedIn or Instagram or Twitter.

For more on extracting wisdom from people with unique perspectives, check out my award-winning book, The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively. Get a copy to a recent high school and college graduate!

Read Intriguing Past Issues Here:

When Goodbyes Are Never Said

If this is your first Provoked newsletter, learn more here Language dictates consciousness. This simple mantra has numerous downstream consequences. It’s why describing what you feel in very precise terms offers a sense of ease in understanding what we feel and then regulating what we feel to get the best possible outcome in the immediate situation.

One of many examples of what is wrong with the field of science. It took approximately a decade from when I knew the results of my dissertation to publishing it in a peer-reviewed journal. If we think psychological science is important there must be a better way. I suggest disseminating results immediately on a website, social media, and in talks. Just be transparent that the write-up (1) is preliminary, (2) should be treated with sufficient curious skepticism, and (3) data are available for anyone who has meaningful questions.

You’ve deftly written what I’ve had an inchoate feeling for some time. I have extensive “Notes” on my iPhone which are indices of ideas I used to have in word files, laptop, disks, cassettes (!) and so on.

I used to have a game with friends where we had lists of predicted technology and dates it might surface, which has been quite fun, still not at the bottom of old lists, and my “Siri command” list is still growing. Technology development paths and outcomes are easy to see.

My experience on internet in research is that for what passes as ideas in some combination of medicine and sociology (take a “gay brain”) is mostly crapola. Hard sciences is ok (e.g. Entropic gravity vs dark matter). AMA declared declared that AIDS would be soon over in the late 80’s kind of thing - can you trust AMA papers? I’m still re-evaluating mirror neurons. My index on trans grows ever more strongly predictive.

I also find strong ideas which may be reasonable get latched onto by conspiracy theorists and the ideas curdle, and hard to discriminate with based on Internet “research”. For example, controlling for a number of factors, people in the US do not show consistent average height growth since the 70’s compared to other countries like Holland. I also have observed cock size in men across the world, at private sex parties, in advertisements and public situations, and American men under 45-55 can be quite a bit smaller than their counterparts. Americans are also fatter across the board… which started in the late 70’s. The explanation I found, the Occam’s razor was xenoesteogens, which suppress height by activating growth plate calcification, can cause anything from hypospadas to breast growth in boys, and have receptors in fat cells which can stimulate accumulation of adipose tissue (I call it the Height Length Width problem) But the world of PFA’s, Atrazine and other chemistry has huge swaths of conspiracy-driven discussion which makes most research to clarify and quantify ideas useless.

Getting people to ask the right questions as they read is so, so hard.

You rock, Todd. 👍