[Note that this post is too long for email. Click on the title of the post to read on the Provoked Substack].

If you seek unconventional insights on well-being + optimal performance, consider this newsletter home (learn more - here).

I love being a psychologist. I love running a research laboratory. I love teaching people what they can learn from psychology. With this mission, however, my heart is regularly broken. Here, I try and capture what bothers me about the field that I’ve been intensely involved in since 1998.

Let me sift through my three biggest beefs. My apologies in advance if this sounds harsh. To fix problems, we must name them. My hope is that writing this improves the research and communication of research - whether it’s writing scientific articles, speaking on podcasts, or posting something in a magazine or LinkedIn.

Psychology Problem #1: The Noise

As soon as I started writing trade books for the general public in 2007, I realized the uselessness of most published peer-reviewed scientific articles.

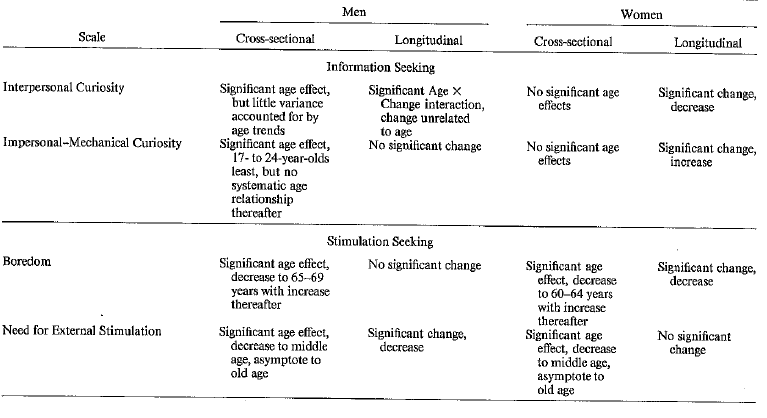

Sifting through research for compelling discoveries, it was hard to be confident that what I was reading matters in the real-world. Yes, I found impressive studies such as how boredom decreases in women over the course of 6-8 years (but not so for men).

For every one of these gems, I found 117 articles that showed nothing more than the correlation between a bunch of surveys given to college students. For instance, I was really excited to write up a section on curiosity in sports. The first article I read showed that college students with a preference for novelty - because they are highly curious - show a preference for watching novel sports. That is, curiosity is correlated with curiosity! If I wrote this for my book on curiosity, what would be the take-away for the reader?

I’ll return to this point later.

Psychology Problem #2: Ignoring Bad Data

I am not the first to point out how it is hard to remove bad science from the field. Take a tour through the terrifying world of retracted science - here.

What I care about is that the public receives proper education about what is known, unknown, with intellectual humility about hypotheses and data originally thought to be legitimate but found to be untrustworthy or unreliable. In the rush to publish scientific findings, scientists push out a lot of bullshit. As of this writing, over 400 scientific articles related to COVID-19 have been retracted for serious errors (link). This includes studies of possible causes and interventions retracted because independent investigators no longer have confidence in the results and conclusions.

It's crucial to understand that the beauty of the scientific process lies in exploring, testing, and refining ideas. Inevitably, there will be a portion of results that don't stand up to replication (or don’t generalize beyond the type of people studied such as WEIRD samples - link). This is expected and integral to the scientific method, particularly when navigating uncharted territories like a pandemic.

It's our responsibility to adjust our belief system when the data fail to withstand rigorous examination. A case in point is the proposed use of ivermectin in treating COVID-19. As of now, at least 11 previously promising articles have been withdrawn due to unequivocal evidence of unreliable findings. Something I wish my cul-de-sac neighbor would listen to me on…

A similar problem exists in the study of psychological flexibility which is what the widely touted Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) supposedly improves.

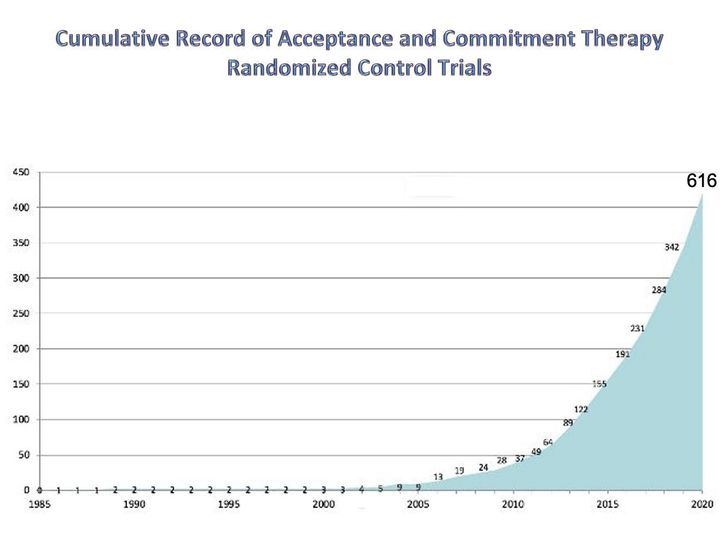

Over the past 30 years, there have been over 600 clinical trials of whether ACT works. And by works, I mean, evidence that the primary target moves in clients: people become more psychologically flexible.

Yet, a not‐so‐hidden problem exists in this large body of work. A large chunk of the literature on the effectiveness of ACT interventions hinges on the use of a single measure, the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ-I - cited 3,237 times; and AAQ‐II - cited 5,178 times), which frankly, sucks. This is not a personal opinion. We found that the AAQ is basically a measure of distress, loading together with other related measures of negative emotions and patient health problems.

What does this mean? Each of those 600 clinical trials relying on a measure that supposedly captures psychological flexibility, but doesn’t, fails to provide evidence that the intervention alters psychological flexibility. What’s hard for researchers, much less the public, is that these problems are ignored when people’s identities are tied to the topic. Consider this 2024 article:

This single paragraph intentionally ignores that despite “over a thousand” trials, the evidence is miniscule “that ACT works through increasing psychological flexibility.” Instead, based on what the measure measures, ACT is much more boring: emotional distress is reduced. That’s a very different storyline. A storyline that is not novel or interesting because therapies have been documenting this effect since the 1960’s. Less novelty means less fame and riches - a perverse incentive to ignore unsupportive data and hold on dearly to Myside Bias.

Psychology Problem #3: Scientific Thinking

Writing lengthy conceptual papers and books, giving workshops to teach people what curiosity or psychological flexibility is and how to boost it, turned me into a more discerning scientific reader. The result? I found myself disappointed often. But this wasn’t the biggest problem.

It is the lack of scientific thinking. A recent issue of

relays the downstream consequences of too few newspapers in the United States and the production of low-information voters. I think there is an analogous problem in psychology.Too many students enter into graduate school with a hyper level of specialization. They want to show that mindfulness training needs to be modified to help Latina/o/X people feel less socially rejected. They want to show how there is a racial bias in police shootings. They want to show that the answer to a fair and safe sporting environment for women is the inclusion of transgender women.

I have seen this change. Students do not enter training program to explore whether mindfulness training works the same in different populations. They know it does and want data to prove this. Often, this leads to studies that do not allow for a test of the null hypothesis - that is comparing, White, Black, Asian-American, Native American, and Latina/Latino students of the same socioeconomic status. There are basic questions that cannot be jumped over. Does mindfulness operate differently in different racial groups? And if so, why? Are there alternative explanations that it might not be due to race?

It’s a good thing that people study what’s important to them. It will help them persevere in acquiring knowledge and skills. But if you are too laser-focused on one topic, you fail to gather generalist knowledge and skills. Of most importance - how to think like a scientist and conduct research accordingly such that you may or may not get the answers you want. In fact, it will probably be inconclusive until more studies are conducted - and that’s not only okay, it’s expected!

Let me end with this wonderful quote about hypotheses that is hard to hold onto but to be curious and intellectually humble in our pursuits, we must:

The hypothesis is a statement of what one doesn’t know and a strategy for how one is going to find it out. I hate hypotheses. Maybe that’s just a prejudice, but I see them as imprisoning, biasing, and discriminatory. Especially in the public sphere of science, they have a way of taking on a life of their own. Scientists get behind one hypothesis or another as if they were sports teams or nationalities — or religions.

Stuart Firestein (2012). Ignorance: How it Drives Science. Oxford Press

I am not a fan of discrimination. This includes discriminatory behavior in science. It perverts the greatest source of information at our disposal to uncover how humans and the world operate. As such, resist producing and sharing noise, resist ego-protection strategies and own up to bad science, and by thinking like a scientist you will be on the path to greater intelligence and wisdom.

If you liked this post, leave a ❤️. Even better, share this conversation and comment with thoughts, questions, or beefs. I love hearing from readers.

Todd B. Kashdan is an author of several books including The Upside of Your Dark Side (Penguin) and The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively (Avery/Penguin) and Professor of Psychology and Leader of The Well-Being Laboratory at George Mason University.

Read Past Issues Here Including:

The Last Acceptable Form of Discrimination

If you seek unconventional insights on well-being + optimal human functioning, subscribe today. Provoked has readers in all 50 US states + 102 countries. Be a paid member and join the Ask Me Anything Zoom call May 30th, 8pm EST.

I have been strugging with the same question ever since my important work was rejected simply because the editor did not like my conception of existential positive psychology as the study of the eternal existential question of how to live a good life, or how to live well in a world full of suffering and evil. Therefore, the problem of what constitutes great achievement is not just bad dada, bad sicence, bad peer review, but asking bad scientific questions,

The fundamentl problem is that most psychologists treat reseach as a scientific game of playing with abstract concepts and proving which concept is supported by most data, This game is basically unfair and counterproductive, because the most creative and beneficial ideas may never see the day light because all the gatekeepers for publications and research funds in the West share the same Eurocentric WEIRD biases,

In the mid 1980s, I was a principal in an “exam cram” video business (SAT, ACT, GRE, LSAT test prep stuff) One of my partners was a PhD psych professor at Tennessee, the other one was just getting his doctorate in psychology. He told me that one of the questions on his exit “general exam“ was “it is often said that psychology is learning more and more about lesson less. What do YOU think?“ LOL.

Re:

“Too many students enter into graduate school with a hyper level of specialization.”