We've Misunderstood How to Evaluate Teachers for 100 Years

Plus Bonus Strategies for How to Get Students to Adore You

Welcome to Provoked - a one-stop source for insights on Purpose, Happiness, Friendship, Romance, Narcissism, Creativity, Curiosity, and Mental Fortitude! Support the mission (here) and get these benefits:

If you’ve ever stepped foot on a college campus as a student, chances are you’ve filled out a teaching evaluation form at least once. It’s the system that supposedly evaluates the quality of your professors and determines whether they get promotions, raises, or even get to keep their jobs. Seems simple enough, right?

Well, it’s a fucking disaster. They’re like a magical unicorn—you hear a lot about them, you’re told they’re important, and then you realize they’re mostly made up of glitter and delusion.

The Science of "Does This Even Matter?"

In the past five years, two very serious studies asked the fundamental question: Are student evaluations just an elaborate way to waste everyone’s time? Turns out, yeah.

Study 1

This one’s a bit of a whopper, with data from 23,000 student evaluations of 379 instructors who taught 1,177 sections. The best part? The evaluations were compulsory, meaning every single student had to fill one out. And here’s the big reveal: the correlation between student evaluations and final exam scores?

Wait for it...

A staggering 0.04. (link)

Yes, you read that correctly. 0.04. That’s not even enough to call it a “barely noticeable blip.” That’s like saying, "Oh yeah, I totally watched 6 seasons of Cobra Kai because the weather was nice that day." In other words, student evaluations are as useful as asking your cat how it feels about your choice of pancake syrup.

Study 2

Now this study (link) involved 2,459 "fully-crossed dyads" (aka: pairs of instructors) from a large university. These two instructors taught the same two courses at least twice over a three-year period. Yes, these researchers were thorough. They were basically trying to figure out which variables influenced student ratings. Was it the instructor? Was it the course? Was it the fact that half the students were probably checking their phones and giving random scores to get the thing over with?

Here’s what they found: a three-way interaction between instructor, course, and occasion accounted for most of the variance in the student ratings (24%). In simple terms, who taught the course mattered—but only a little. The rest of the variance? Well, a lot of it was determined by other stuff.

Stuff like the weather that day, how tired the students were, whether they didn’t eat lunch and were in a bad mood. So yeah, factors completely unrelated to actual teaching quality played a bigger role than the professor’s ability to teach. Go figure.

The Science Takeaway?

The studies are saying that student evaluations are like your friend who always gives advice on what to wear but has zero sense of style. Not super reliable. 0.04 correlation? That’s like buying a lottery ticket and being shocked when you don’t win. It’s the same outcome every time: you’re not getting anything useful from these evaluations. So next time someone tries to tell you that the student evaluations are “definitive” proof of anything, remember: those 0.04 points probably came from someone who was just happy they didn’t have to do any homework that week.

These evaluation scores don’t measure teaching effectiveness—they measure who’s likable. And yet, universities have been using this broken, ineffective system for over a century. We’re talking about a system that still thinks giving students the power to grade their teachers anonymously is a good idea. Great for trolls, bad for cooperative societies.

When Student Evaluations Were Born (A Strong Case for Contraception)

It’s the early 20th century. The world is finally getting its act together, mass-producing everything from cars to canned soup to, naturally, education. A gaggle of earnest, tweed-wearing academics—most likely adorned with pipe smoke and thick glasses that made them look like they’d just stepped out of a Sherlock Holmes novel—decided they needed a surefire way to assess teachers. So what did they come up with? Student evaluations.

Sounds like a good idea, right? "Surely," they thought, "students know best about whether the teaching is any good!" After all, they were the ones suffering through interminable lectures on obscure 18th-century literature or the precise difference between ionic and covalent bonds. But, here’s the twist—even the people who designed these things warned us it was a terrible idea.

In the 1920s, the very scholars who came up with the concept of student evaluations—probably over a couple of scotch drinks, their beards twitching with excitement—cautioned that the system might turn into a glorified popularity contest. And they weren’t wrong. One of the early researchers, Professor William E. Henry, reportedly said, "Students will be swayed by the teacher’s personality, not their teaching skills, and this will render the system completely unreliable." But did anyone listen? Nope. The wheels were set in motion, and universities hit the big red GO button like a group of overzealous undergrads in a finals week caffeine-fueled frenzy.

The "Popularity Contest" That’s Ruining Everything

And so, the Student Evaluation of Teaching system was born. With lofty aims to improve teaching quality and hold educators accountable. “It’s about improving instruction,” they said. “It’s about feedback,” they said. But it didn't take long for this “revolution” to unravel. A d bunch of well-meaning but hopelessly naïve folks produced the actual problem: perverse incentives.

Let’s be real—students love easy A’s. They’re not shy about it. And if you want to get into a competitive graduate program, you pretty much need a GPA of at least 3.7 - which means every course must lead to an A- or A.

Here’s how it works: Students need good grades, and faculty need good student rating scores. The result? Teachers who are good at getting high evaluations don’t necessarily teach better—they just know how to play the game. So, what does every savvy professor do? They start hacking the system.

Want to boost your ratings? Easy. Here are foolproof ways to ensure student evaluations glow as a neon sign in a blackout:

Turn off the lights and play videos: Nothing beats a classroom “teachable moment” like watching entertaining YouTube clips. Learning? Optional. Shoot, I just showed this Key & Peele skit in my last class. If you want to know the context: it was a class on the benefits of positive emotions. First, I raised everyone’s physiological arousal. Second, I had them measure their heart rate. Third, I showed them this video to illustrate the “undoing effect of positive emotions” (link). (Message me in the Premium Chat room and I will provide more details - here)

Snow Day for 0.002 inches: Declare a snow day if there’s even the slightest chance of precipitation. They’ll think you’re a hero.

Pop quiz, no grades: Instead of taking attendance, tell everyone there’s a quiz. Ask them to pull out a piece of paper and a pen. Add a pregnant pause. Then verbalize question number one: “Write your name.” Tell them, that’s it, hand it in. One-question quiz! “Everyone’s a winner!” Bonus: no actual work for you.

Give surprise “extra credit”: Your evaluation score will rise like a rocket when you throw in some random bonus points. Give some random self-affirming reason: “You’ve been attending class and asking great questions and making great comments, this is a reward for you!”

Introduce breaks: Just like nap time in kindergarten, offer a mid-class break. Who needs lectures when you can have them tear around on scooters outside for 10 minutes? Offer the science of work breaks (link) and exposure to nature (link) to renew energy and focus! Go eat a protein-enhanced pop-tart, catch up on your email, and think of how high those scores will be now!

Celebrate obscure holidays involving sneaks: Did you know it’s National Steakburger Day? Throw a class party and offer extra credit for “participating.” Chips, cookies, whatever. Offer free snacks and you’ll be the most beloved teacher on campus. Dr. Alice Isen showed us how this works - here.

Late-start days: Announce that class will start an hour late because “everyone needs their sleep.”

Let them out early: Let students leave class five minutes before the bell. They’ll love you for it. Nobody asked for someone to talk longer, and that might even include you,

!

But while professors were raking in the easy student evaluations, the whole thing became a game of trying to look cool. The ones who played it safe were rewarded, while those who took risks, challenged their students, or forced them to put in actual work were punished with lower ratings.

And here’s the sick part: universities know all of this and keep plowing ahead. But the idea that you could measure teaching effectiveness based on how well you could entertain a bunch of students, who were only there for an easy pass, was something the very creators of student evaluations warned about.

The Biases We Don’t Talk About

But it’s not just about making class easier or giving out snacks. There are pretty nasty biases hiding under the surface.

When students fill out evaluations, what do you think they’re evaluating? The teacher’s content? No. They’re evaluating the teacher. And let’s be real—just like in the dating world, people are biased.

Sizeism: Shorter professors? Don’t even get me started. The taller you are, the more “authoritative” you are in students’ eyes. That’s just the shitty reality.

Sexism: Female professors, especially those who aren’t considered conventionally attractive, don’t get the same ratings as male peers.

Racism: Professors who aren’t White are penalized on these evaluations, even if their teaching is on point.

Ableism: Disabled professors, especially when visible, often get worse evaluations, regardless of their teaching skills.

Ageism: Older professors are often seen as “out of touch” or “too traditional,” regardless of their experience or knowledge.

It’s basically biases 101—whether you’re dating or trying to get hired, the game is rigged. Same shit happens as a teacher. And none of that has anything to do with teaching skills.

Time for a Change

What followed was the inevitable. Grade inflation. Easier courses. A decline in actual teaching quality. And the students? Well, they continued to reward professors who gave them the easiest ride. The entire system fed itself, and what was meant to be an objective measure of teaching quality turned into a massive popularity contest.

But here's the irony: the folks who created the evaluation system in the first place—those earnest, pipe-smoking tweed enthusiasts—had great intentions. They thought this would help improve education. But they underestimated one thing: humans are fucking lazy. And when you give people the power to decide who gets promoted or who gets fired, they'll choose the easy path.

In the end, they created a convoluted system where professors who made it easy to like them were rewarded, and the ones who did their job of teaching effectively were punished.

So yeah, here we are, 100 years later, stuck with a system that hasn’t evolved. But now that we’re aware, maybe it’s time to give it a proper “snow day” of its own. Or better yet, let’s just put it out to pasture with a nice, polite “thanks for your feedback” email, then quietly pretend it never existed.

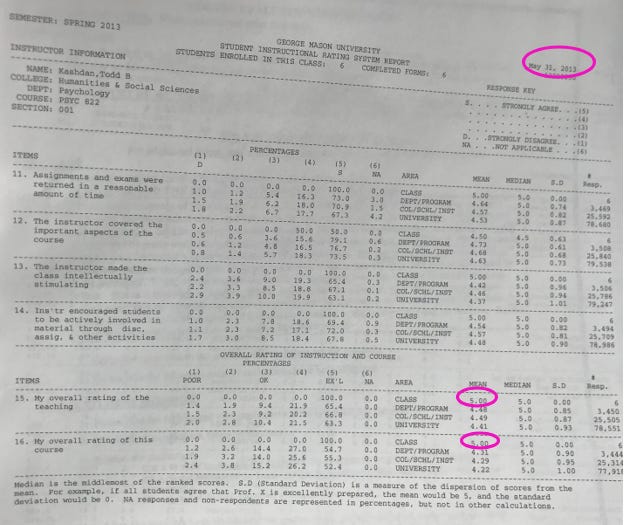

As someone who received several 100% perfect student evaluations of my teaching (anonymously) from 2013 to 2024, I realize it’s all a game.

Share this so that teachers who help students learn best are properly evaluated + rewarded:

Share this on social media and send it to friends;

Leave a ❤️ and comment;

Subscribe (with benefits such as the chat room and 200+ article archive).

Upgrade to Paid Subscriber and join conversations in our premium chat room:

Extra Curiosities

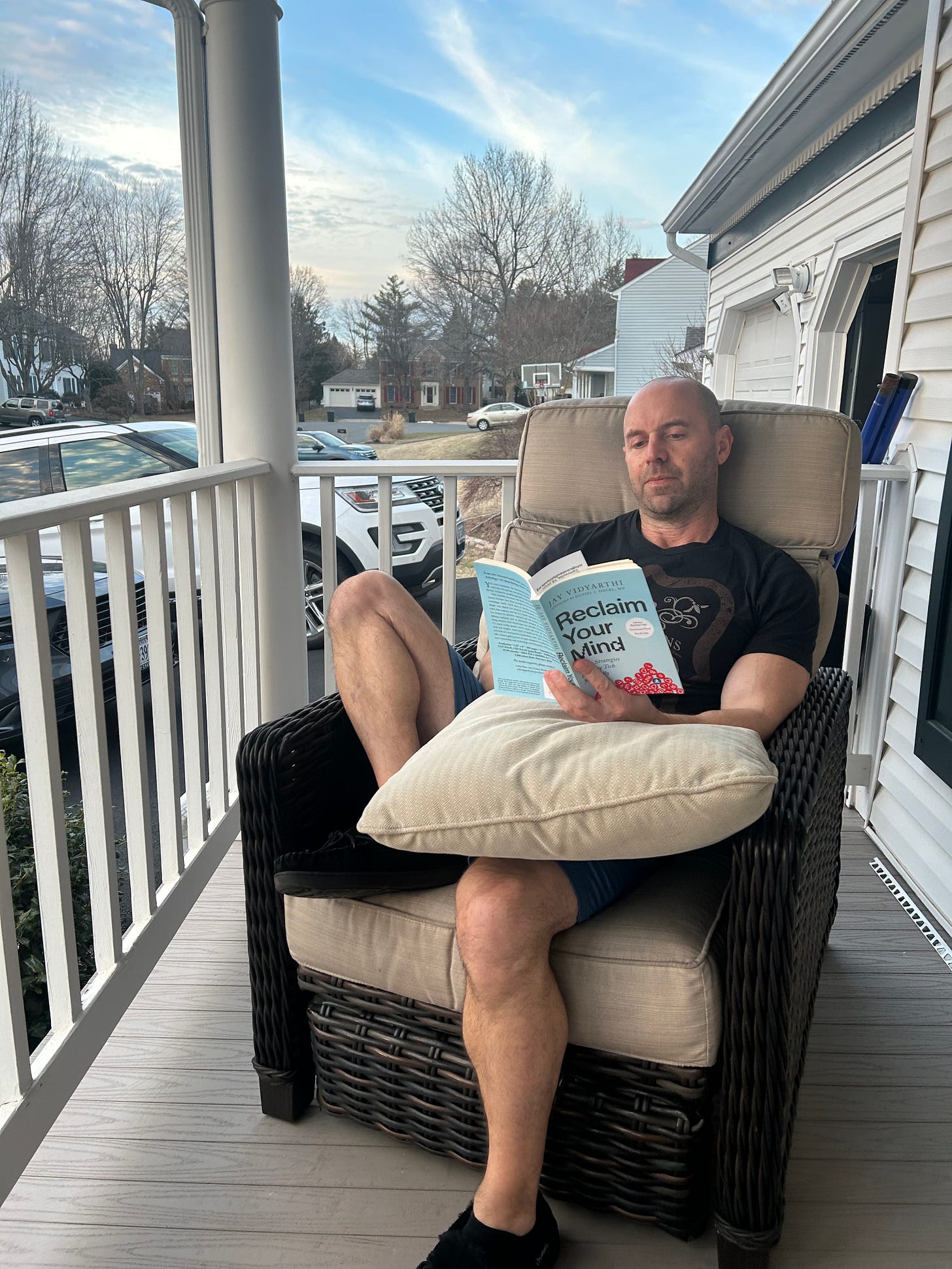

What I’m Reading Now and Why - If you’ve been caught in the tug-of-war between those who want to ban smartphones and those comfortable letting their kids turn into mindless cyborgs, Jay Vidyarthi’s Reclaim Your Mind is the antidote (Link). I’m not going to mince words, I love

‘s brain. He offers a playful, grounded approach that helps us break free from the guilt and confusion that come with tech. This book isn’t about demonizing technology or blindly worshipping it; it’s that sweet spot where you can use tech thoughtfully - as it’s just a tool.

Todd B. Kashdan is the author of several books including The Upside of Your Dark Side (Penguin) and The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively (Avery/Penguin) and Professor of Psychology and Founder of The Well-Being Laboratory at George Mason University.

Read Past Issues Here Including:

I Have a Theory on How to Treat Depression

Welcome to Provoked - your one-stop source for insights on Purpose, Happiness, Friendship, Romance, Narcissism, Creativity, Curiosity, and Mental Fortitude! Support the mission (here) and get these benefits:

Not in the US system so don't feel valid commenting on the more general aspects of this, but when it comes to women, I wonder how that would break down if analysed by field?

Anecdata for sure, but I've studied across four different disciplines and three different universities for a cumulative amount of undergrad years that is too embarrassing to admit, and I've seen massive variance in both gender ratios and relating to students depending on the faculty. Psych draws mostly female professors who have been, with the exception of one in I/O, an absolute nightmare to deal with. The few men were... fine, if a bit browbeaten by their colleagues. No Todd Kashdans anyway. On the other end, sports sci is very male dominated. The women in their midst are some of the most amazing humans I've ever had the fortune to meet (and barely a YouTube video in sight).

I guess I'm thinking, (and stats is not one of my fields...) that if the majority of students these days are female, and they're choosing, as they are, subjects where women are over represented in the faculty, and the gender imbalance there causes some sort of intrasexual competition/female dominance hierarchy/relational aggression that contributes to a culture that is less than ideal for the student body, then that data seems fairly valid, based of course on my entirely invalid n of 1.

At the end of the semester, I like to ask the students to provide direct feedback. And they usually do.

The student evaluations always sound like that this big giant that has the power to can out teachers. And not always as you eloquently say, the best evaluations aren't for thr best teachers.

And one thing also is for certain, they have also molded students. Curiosity looks a bit dormant on them and a lot of times they want the easy or predictable road. Even when I do fun stuff, they ask "when are we going to have a test"? As if tests were the only way to learn. Go figure.