On the Difference Between You and Criminals

What Gets Neglected in Conversations About Social Justice

A friend of mine, a U.S. Marshal,1 shared a story about the only criminal that scared him. In a daring prison escape, a criminal shoved a pistol into a guard’s forehead and pulled the trigger. Somehow the bullet cartridge jammed. The guard survived but was never the same.

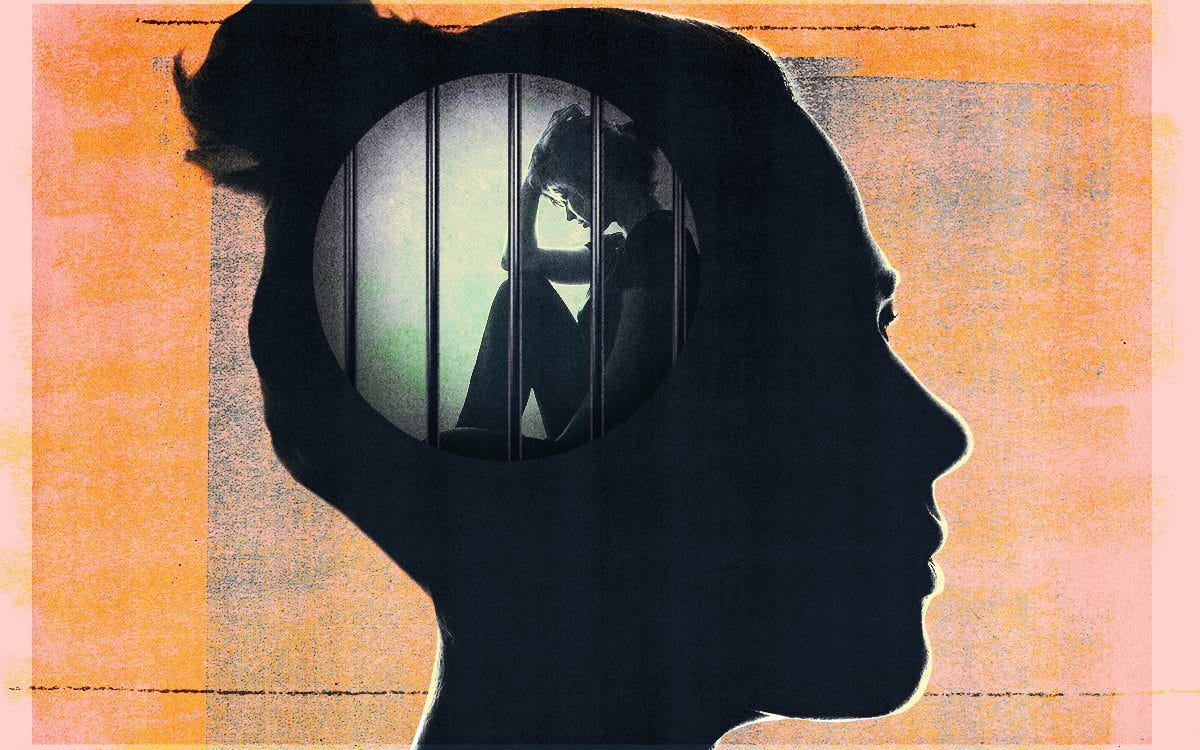

Imagine what it must feel like to expect premature death by a violent criminal. You survive but that sense of safety disappears.2 Instead, every social situation is infused with hypervigilance. Danger could arise anytime from anyone.3 If the building blocks of a fulfilling life are moments, your mind gives them away freely in exchange for a continual concern about self-preservation.

Here’s the unfortunate ending: If the gun discharged, the prison guard received ample financial compensation. Without an injury, however, the prison guard received nothing. He never worked again. He has been in perpetual mental anguish.

Luck determined the outcome.

The criminal intentionally fired the gun in hopes of a kill. A lucky mechanical failure saved him.

Why should luck be a huge determinant in our justice system? We can be grateful that a death did not occur and compensate a man experiencing emotional difficulties because of an event that should have never happened. Someone has to be the defender of justice. Instead of platitudes (“thank you for your service!”) we should remunerate them for investing in their services. We should help them with money, healthcare, and whatever allows them to live as they once did as a fully functional member of society.

We Are All Criminals

You have driven faster than the posted speed limit. You have been distracted while driving. Maybe you used a smartphone for a call or text. Maybe you wrangled with the radio station or temperature gauge. Maybe you applied makeup or futzed around with a GPS.

Six out of 10 Americans admit driving past the speed limit. More than half of Americans think it’s acceptable to drive and talk on a hand-held cell phone. Although nobody is in favor of killing someone, vehicular manslaughter resulting from distractions is punishable for up to 20 years in prison.

As other people receive punishments in terms of fines, suspended licenses, and prison sentences for breaking road laws, you escaped scrutiny.

Luck determined the outcome.

You just happened to receive less attention from police officers at the right moment.

The value of bringing luck to the forefront of the criminal justice system is an installation of compassion, mercy, and forgiveness.

Before transgressions occur, there is meaningful overlap between us and fellow drivers. They might do a morning functional mobility routine to the sounds of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon. They might re-read Haruki Murakami books, especially Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. But as soon as they receive jail time, they are othered, members of an outgroup unlike our own social circle. We are solid members of the community whereas they are criminals.

It is these mental categorizations that allow for prejudice to creep in. With activated biases and stereotypes, perhaps we discriminate against them - the criminals among us. We might be less inclined to hire them, lend them money, or have them near kids. The one feature that makes them different looms larger - luck.

Punished drivers experienced a different situation while executing the same behavior as the majority of the population.

In an era of public shaming,

In an era of judging human beings with the least charitable interpretation,

We can acknowledge a historically known truth:

The flaws despised in others often reflect our own.

Our approach to addressing errors, mistakes, failings, and vices is worthy of an overhaul - from individual condemnation to entry into the criminal justice system. You are not so special. Luck plays a huge role. Reconsider that disproportionately harsh, swift judgment.

Explore THE ART OF INSUBORDINATION

If you enjoy this free newsletter, please check out my award-winning book, The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively. This book will teach you 10 things about how to change minds (here). I’d be grateful if you picked up a copy for someone seeking greater mental fortitude and persuasion skills. Or a young adult who wants to amplify their voice. Or minorities (lacking power and status) in the workplace. Or leaders who want to better manage disagreements and challenges to conventional thinking. This is a guidebook for making groups smarter.

And If You Missed the Last Issue…

My favorite fact about the U.S. Marshals is that they had the task of escorting 6-year-old Ruby Bridges to school in 1960. Ruby Bridges, the first Black child to desegregate a southern elementary school. Nobody touched her because of those three men. I do wish they pointed a stern finger in the face of a few of those white parents spitting racial epithets and calmly said, “Ma’am, I’m going to need you to shut the fuck up, right, fucking, now…one of us is going to look like an asshole in these pictures and it’s not gonna be me.”

Related work finds that after losing a job, many men never return back to their prior happiness levels. Their baseline happiness warps.

Known as a sense of looming danger. Check out this wild body of research by my colleague, Dr. John Riskind.

I wonder if any research has been done to look at individuals in similar circumstances who went on to live as if (fairly) unaffected by such a shock? In other words, was their internal dialogue different? If one believes that the incident was not a circumstance of luck, but of intelligent design that you have a purpose (yet unfulfilled), did that thought process generate better emotional outcomes? And I think that kind of dialogue is more powerful than thoughts expressing "It wasn't my time."