Some psychological topics become popular to the point of boredom, such as intellectual humility. "Be humble, and proudly" says psychologists in The New York Times. Get "a lesson in intellectual humility" in The Atlantic. And of course, a 15 minute TED Talk on "the power of intellectual humility." All of this gives the illusion that we know intellectual humility well. But ironically (in the vein of Alanis Morissette), we know less than we think.

The Unsung Hero of Intellectual Growth

Imagine you're at a dinner party, and the conversation turns to a topic you're passionate about - bodybuilding with resistance bands, not dumbbells or barbells.

You're ready to jump in with well-reasoned arguments, but then you pause. You realize there's a chance you could be wrong. That pause, that moment of self-awareness, is the essence of intellectual humility (IH).

It's not just admitting you might be wrong. It's recognizing the vast expanse of what you don't know, and appreciating the intellectual prowess of others.

If you're the dinner guest, you probably recognize this is a desirable quality that draws people in. If you're at the party, you probably find this quality to be far more attractive than narcissistic bragging that is all-too-common in social gatherings. We tend to think of IH as a personality trait, even a character strength - something that lives inside a person, like a little humility homunculus pulling the strings.

The Core

Think of IH as the quiet, thoughtful scholar in the corner of a bustling library. It's not about doubting yourself or lacking confidence. It's about holding beliefs lightly, ready to revise them when new evidence comes along. It's about understanding that your perspective is one lens through which to view the world. A lens might be smudged or even cracked.

Now, you might be thinking, "Isn't this just humility?" Well, not quite. Imagine humility as a tree, with many branches representing different aspects. IH is a branch. While general humility involves a broader view of oneself in relation to others and the world, IH is specifically about our beliefs and attitudes. It's about being humble in our intellectual pursuits, recognizing our knowledge has limits. It's about a desire to gain knowledge, not conviction. A desire to seek out safeguards against mental errors and biases.

IH can be a fleeting state, like a brief pause in a heated debate, or it can be a more stable trait, like a consistent approach to learning and engaging with others. It's like the difference between a single note and a recurring melody (Exhibit A - my current, favorite gentle tune: click here). While we all have moments of intellectual humility, for some of us it’s a recurring theme in our intellectual engagements.

But what if it's not just about us as individuals? What if intellectual humility is also about the groups and cultures we're part of?

The Collective Side

Yes, IH is about knowing your limits, recognizing your mistakes, and being open to new ideas. But that's only a partial description.

It's about how we, as a group, create an environment that encourages humility, that values questioning and curiosity, and that isn't afraid to say, "Hey, I am definitely not the smartest person in the room, so where is my thinking off?"

This idea is in line with some of the latest psychological research. There's a growing recognition that traits we usually think of as individual—like implicit bias or a growth mindset—might be better understood as a product of our social environments than about us as individuals.

Take implicit bias. A contentious topic. The conversation often focuses on individual biases that each of us carries around. But what if we zoomed out? What if we looked at how social environments—schools, workplaces, communities—shape and reinforce these biases?

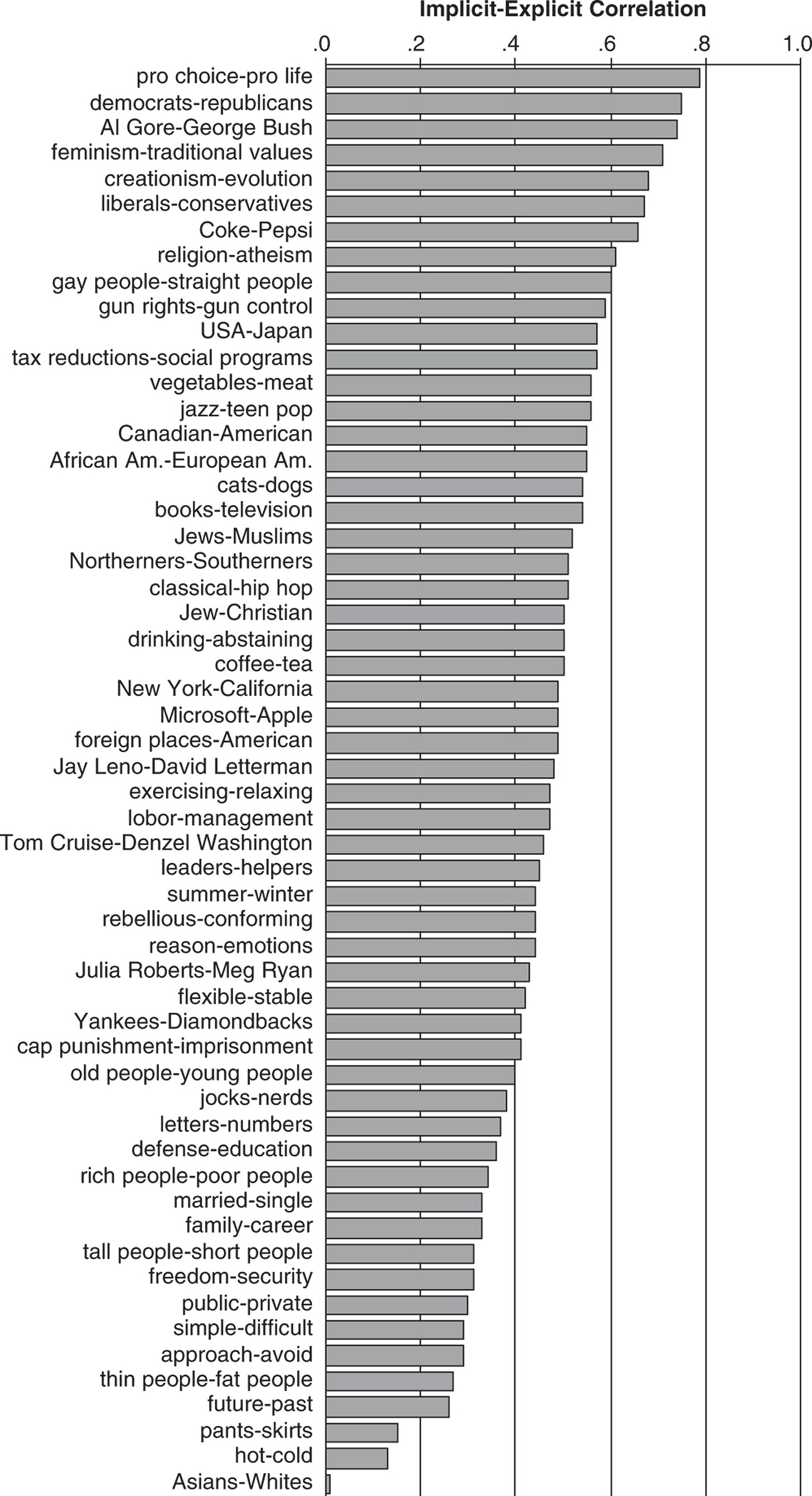

Consider the Implicit Association Test (IAT), a popular tool for measuring implicit bias over the past 25 years. It's often used to give individuals feedback on their level of bias. You can test for rapid likes and dislikes on the fringes of conscious awareness toward almost anything. Sometimes your implicit bias is highly related to your conscious thoughts and actions. If you show an implicit bias against eating a Japanese Wagyu Ribeye then you are very unlikely to eat it. However, if you show an implicit bias against overweight people you don't behave much differently than people who lack this implicit bias (see the published data below).

Perhaps the IAT says little about individuals. Our biases might be better understood as products of the cultures we're part of. This point is captured by Dr. David Dunning (named entity of the Dunning-Krueger effect, which might not be real):

In studying implicit bias, psychologists assess attitudes and prejudices a person may harbor toward other racial groups that lie outside of their awareness, intention, and control (Kurdi et al., 2019). However, in developing scientific measures of this disposition, such as the implicit association test (IAT), a few issues have puzzled researchers. Such measures often fail to exhibit the statistical signatures expected of a meaningful disposition on which individuals differ. Implicit measures tend not to correlate that highly with behaviors they should predict, nor do they stay stable over time – as would be predicted if they reflected unwavering individual dispositions (Payne & Hannay, 2021). Implicit measures correlate with one another inconsistently (Brauer et al., 2000), and with more explicit measures (i.e., those under the control and awareness of the individual) only modestly (Hehman et al., 2019).

However, if one examines implicit bias at a more collective level, the statistical signatures of a disposition emerge. At the county level, temporal stability of implicit attitudes emerges – even more so at the level of urban metropolises or American states. Strong correlations between implicit and explicit attitudes also emerge as one moves from the individual to state level (Hehman et al., 2019). Further, at levels of the collective, implicit bias measures begin to correlate meaningfully with behavior. For example, college campuses with higher bias scores among its students are more likely to display Confederate monuments and to possess lower diversity among its faculty (Vuletich & Payne, 2019). Disproportionate use of lethal force by police against black citizens correlates with anti-black implicit bias when metropolitan areas in the United States are compared (Hehman et al., 2018). These findings have led to a new assertion that implicit bias may not represent personal attitudes but rather a set of expectations and associations coming from the social environment people are embedded in (Payne & Hannay, 2021; Payne et al., 2017), although this emerging perspective does draw contention (Connor & Evers, 2020).

A Cultural Lens to Psychological Strengths

Take a look at different professions. They often have specific norms and practices designed to keep intellectual arrogance in check and promote humility. Or, maybe you wish you worked at one of these amazing, rare organizations (surprisingly rare in higher education).

Think about the checklists pilots go through before takeoff, or the differential diagnoses that doctors use to make sure they're not missing alternative explanations for a patient's symptoms. These aren't just about individual humility; they indicate a culture of humility.

So, let's start thinking about intellectual humility and other psychological strengths such as curiosity and creativity in a new way. It's about us. It’s about social environments. It's about creating an incentive structure where humility, curiosity, and perspective taking are honored and hopefully, replicated regularly (read Chapters 8, 9 and 10 for interventions). Because intellectual humility will grow in teams faster from norms, not private masterclasses.

Be careful about what you reward and punish, especially in public settings.

Be careful about incentivizing bad behavior by giving a free pass to problematic precedents.

Lessons that many organizations must take seriously - from the fiasco at Harvard University to the Supreme Court.

The presence of a few intellectually humble individuals rarely counteract the adverse consequences of a rigid thinking, highly entitled, hypocritical group.

Provocations

Here are some thought experiments to provoke deeper thinking.

The Inequality Proposition: You're part of a debate where the proposition is that society functions more efficiently when there's inequality between men and women, a belief you've always disagreed with. The arguments presented are logical and backed by data. How do you engage in this debate while maintaining your intellectual humility?

The Unseen Consequences: You discover a study that suggests actions you believed were harmless are actually causing significant harm to the environment, but the effects won't be visible for another 100 years. This challenges your belief in the immediacy of cause and effect. How do you adjust your beliefs and actions in response to this new information?

The Cultural Exchange: You're immersed in a culture with beliefs vastly different from yours. How do you navigate conversations about deeply held beliefs?

The Historical Revision: You discover that a historical event you thought was true is widely disputed. How does this affect your trust in historical knowledge?

Each of these scenarios challenges us to consider how we handle being wrong, how we react to new information, and how open we are to different perspectives. If it was easy, we wouldn't have disagreements with people who differ from us. And it wouldn't be so damn meaningful.

Provoked is free today. But if you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing.

If you are a free subscriber, upgrade for the full experience. Access a number of paid subscriber only posts, provocations, exercises, videos, & Zoom calls.

Dr. Todd B. Kashdan is an author of several books including The Upside of Your Dark Side (Penguin) and The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively (Avery/Penguin) and Professor of Psychology and Leader of The Well-Being Laboratory at George Mason University.

Connect on: Twitter or Facebook or Linkedin or Instagram or Threads.

Read Past Issues Here Including:

The Unusual Suspect in Political Elections: Pain Sensitivity

In the run-up to the upcoming presidential elections, pundits are busy dissecting poll numbers, analyzing campaign strategies, and predicting voter behavior. But there's one factor they're overlooking: pain sensitivity. Yes, you read that right. Our physical pain threshold might be influencing our political leanings. Sounds like a wild idea, right? But …

"Always check your six."

Don't mean to brag, but after over 25 years in software, this humility has been drilled into me daily. I'm the king of humility. The humblest!