Know the Difference Between Coddling and Cautious, Critical Thinking

Lessons from a School Shooting Threat

“Don’t come to school Mar. 16 I’m shoot this hoe up!!”

This is the vague graffiti written on the bathroom wall in my twin daughters high school on March 14th, 2023. As you can imagine, parents in my neighborhood had a variety of responses.

The Sentinel - is adamant that protecting kids is a priority. They will not send their kid to school. It is an authoritarian decision announced publicly and proudly.

The Tough Guy/Gal By Proxy - treats their kid’s decision as a marker of courage. Thinks kids should/must go to school or else whoever made this vague threat wins! Emotions and thoughts related to vigilance are dismissed. They send their kid to school. It is an authoritarian decision announced publicly and proudly.

The Industrious - conducts a cost-benefit analysis. The principal wrote an email stating, “Police continue to investigate the incident and have not found any additional evidence supporting a threat to the school. However, additional security will be at the school on March 16th out of an abundance of caution.” The parent recognizes uncertainty about the credibility of evidence available. Upon synthesizing the information, they will not send their kid to school. It is an authoritative decision.

The Pragmatist - realizes that the school is probably the safest place in the entire state on March 16th. Despite the vagueness of the threat, the principal said that “out of an abundance of caution, there will be additional FCPS security and police presence both on campus and nearby on regular patrol in the community.” The day before, police could be found on campus, searching the grounds and speaking to staff and students (letting the kids pet police horses). The parent sends their kid to school.

The Normie - waits to see what other people do. Extra weight is given to the decisions of socially attractive people. Based on this external monitoring, they decide yes or no as to whether their kid attends. The kid is left wondering what their parent decides.

The Autonomy Supporter - tries to understand their kid’s perspective. They open up a dialogue and offer their kid a voice along with the role of final arbiter. They permit their kid to attend school. Moreover, they empower their kid to leave if for any reason they feel uncomfortable (no questions asked). It is a dynamic decision that is open to revision.

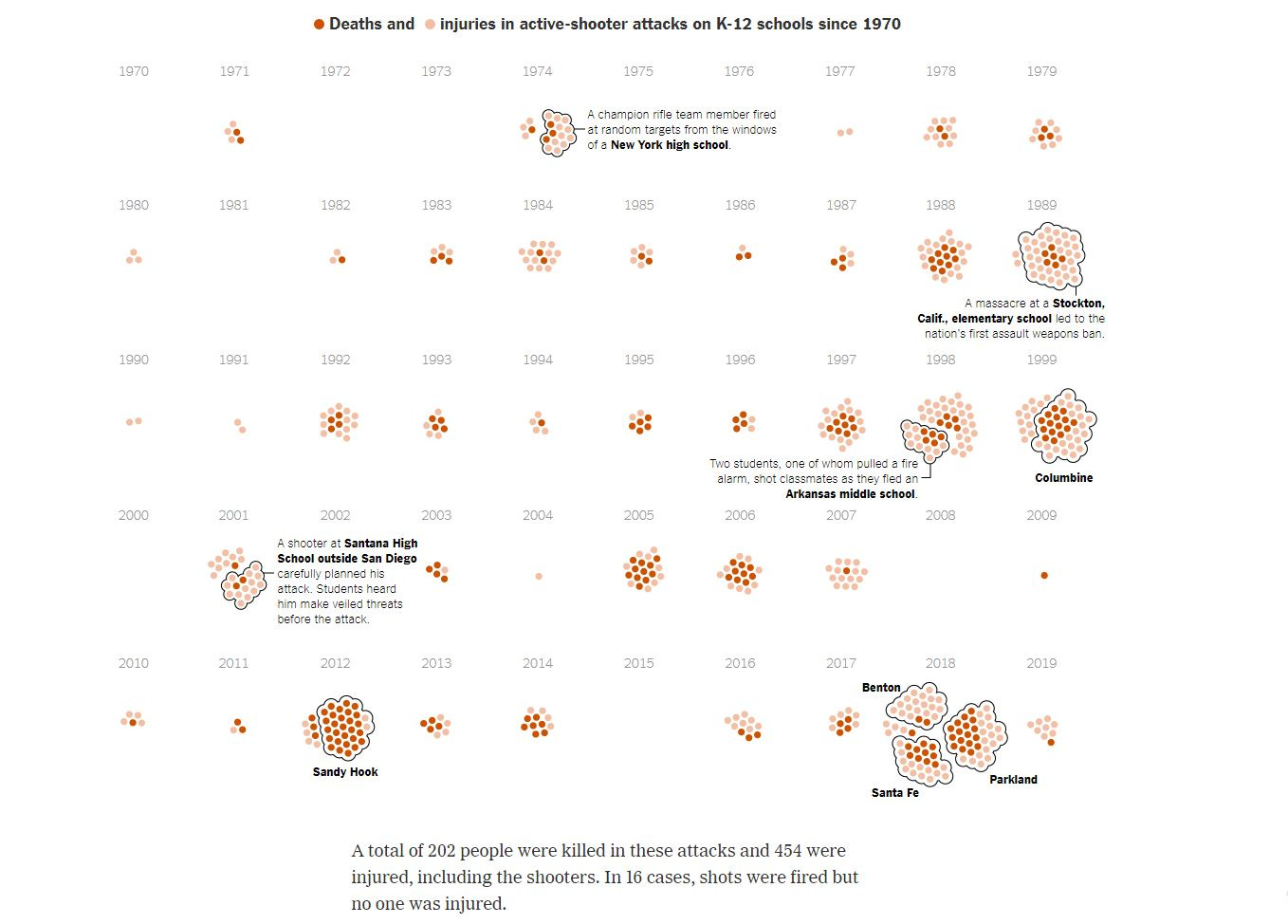

It would be disingenuous (the 8th deadly sin) to claim there are no right or wrong answers for responding to a violent threat. School shootings are low probability events but happen far too frequently in American society.

Psychologists are fond of the formula B = f(P,E) where behavior is a function of a person and the situation they are in. But not all situations are equal.

In weak situations, the person and their genetics, personality, and life history, are primary determinants of what happens. Think of 10am on a Saturday afternoon with nothing on the calendar - not a kid in sight who asks for a ride, not an adult nearby to make you feel guilty for foam rolling stubborn hamstrings with a mouthful of Pringles. Options seem limitless.

Situations are strong when cues about what would be desirable are unambiguous, behavioral expectations are clear, incentives exist for compliance with expectations, and people possess the capacity to meet demands asked of them. A strong situation can be likened to “being in a theatrical production in which the script provides strong cues about what to do.” Think of a restaurant dinner with friends. Even if you are not hungry, you are likely to order a dish or munch on something. The environment pulls for default behavior patterns or habits.

A vague school shooting is a rather weak situation. And this is when we revert to well-learned habits and impression management. That is, we don’t just want to make a successful decision (whatever that means to us), we also want to strategically alter how other perceive us as:

likeable and socially desirable

competent and intelligent

ethical and principled

Parents are no different, especially in precarious situations where it feels as if one’s character and flaws are visible to others.

View Difficult Situations as Precedents

What you decide to do is far less important than the process of how decisions are made. When deciding on high school attendance, the household is composed of authority figures (parents) and dependents (adolescents).

Consider these questions :

How is information collected and evaluated?

In what ways did you give your adolescent permission and encouragement to form their own views? Allow them to dissent from your position?

How are you providing opportunities for open discussion prior to decisions?

How are discussions led?

How are comments attended to?

What behaviors are deemed unacceptable?

How is consultation decided upon and used?

How are the prior guidelines communicated?

How are you modifying the prior guidelines for this exact situation, including urgency?

How are you taking your kid’s psychological needs to feel a sense of autonomy, belonging, and competence into account?

In what ways are you attuned to the developmental growth of your kid, resisting the temptation to treat them as a secondary citizen in the household?

Running a household can be likened to an organization where there are many decisions to be made, and there is a sense of what success and failure looks like. If you have multiple people involved, a group exists. Thus, much can be learned from our knowledge about how to design smart groups.

Scaffolding Instead of Coddling

Much has been written about the problem of adults coddling youth. The impulse to keep youth safe is a well-intended behavior. But the influx of parents trying to bubble-wrap youth has costs. Confusion, frustration, and doubt are critical to learning. Remove these emotional obstacles and you stunt social-emotional development. That said, do not confuse cautiousness with coddling.

There is nothing wrong with trying to avoid danger. But resist imposing your own fears onto others. Empower other group members to be part of the decision-making.

Explain the rationale behind your thinking.

Give sufficient space for every group member to have a voice.

Collaborate on decisions, with consideration of the trade-offs behind available options.

Offer ample opportunity for them to use their voice.

If voicing opinions is relatively foreign to them, be cautious when judging. Do not expect them to be as articulate or emotionally regulated as you. Punish them for speaking up and you can be assured of one thing - lost access to their most important thoughts and feedback in the future. So be gentle. Be compassionate. Be curious. Listen intently for the message and thank them for their participation. This is not coddling, this is scaffolding - where you offer support for their current skill level, and as they learn and develop, revise standards and support accordingly.

Stick to these principles and you will accomplish something far better than problem solving. You will create a precedent for youth to think deeply and carefully on their own, seeking wise council as needed. Maybe, just maybe, you will be asked to be part of that wise council. That’s what I’m aiming for…

Explore THE ART OF INSUBORDINATION

If you enjoy this newsletter, please check out my award-winning book, The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively. This book offers insights on how to change minds when you are in the minority (here and here). I’d be grateful if you picked up a copy for someone seeking greater mental fortitude and persuasion skills. It’s for young adults learning to find and amplify their voice; employees (lacking power and status) in the workplace; and leaders who desire more productive conflicts. This is a guidebook for making groups smarter.