How Curiosity Boosts Memory, Creativity, and Well-being

An overview of fascinating psychological discoveries

[NOTE: escape the paywall of a recent article by Dan Jones on the new science of curiosity where he interviewed Drs. Celeste Kidd, Jacqueline Gottlieb, Matthias Gruber, and me]

DURING an icy April in 1626, Francis Bacon, philosopher and a pioneer of the scientific method, was riding through the snowy streets of London when a curious question popped into his mind: would the cold help preserve a dead chicken? After acquiring one from a nearby household, he set about stuffing the bird with snow. In the process, he caught a chill, quickly followed by pneumonia and death.

This possibly apocryphal story, spread by philosopher Thomas Hobbes, points to two faces of curiosity: one a virtue, the other a vice. Curiosity is the driving force behind science, exploration and discovery, in which form it has been as important in our species’ success as our intelligence. Curiosity can also be a boon to us individually, guiding us into passionate, purpose-filled lives – think of relentlessly curious people like Leonardo da Vinci.

But “the lust of the mind”, as Hobbes dubbed curiosity, turns vice-like when it leads us to waste time on clickbait and fake news, doomscroll through social media feeds or chase dangerously extreme experiences, like jumping from tall objects with a parachute, simply because we want to know what they feel like. It can end badly. Just recall the infamous, now-deceased cat.

In a modern world awash with many such diversions, it would be good to know how to make the most of our curiosity while avoiding its pitfalls. Recent research on the double-edged nature of curiosity is riding to the rescue. The work hasn’t only shed light on its many benefits for learning and creativity, but also on the reasons that it can lead us astray – and why we should sometimes seek to curb our curiosity.

While curiosity is undoubtedly a complex psychological state, most researchers broadly define it as a drive to know things and gather information about the world – something that all organisms need to do. “Information is as fundamental for life as energy,” says cognitive neuroscientist Jacqueline Gottlieb of Columbia University, New York. “A nematode worm or amoeba gathering information about its environment, like where it can find food, shows curiosity, even if it’s a very limited and immediate kind.”

Curiosity in humans – the planet’s preeminent “infovores” – can be more expansive, open-ended and powerful. But, at its most basic level, our hunt for information is sparked by a desire to deal with uncertainty, by seeking meaningful patterns in our surroundings.

Recent research suggests that this is particularly important for babies and children navigating their brave new world. Celeste Kidd, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has devised a series of visual scenes of varying predictability. These videos showed objects like toy fire engines being momentarily hidden by a screen that was repeatedly dropped and raised in front of it. Each time the screen lifted, the object would be present with a certain probability. In some cases, the object was almost always present, making the sequence very predictable, while in other cases the chance of it reappearing was much more random, with low predictability. They also saw scenarios in between.

Kidd then measured participants’ attention with eye-tracking tools to find out exactly where they were looking. In children as young as 7months old, she found that sequences of intermediate predictability elicited more visual exploration than either tediously predictable or confusingly random sequences.

Kidd describes this sweet spot between predictability and uncertainty as the

Goldilocks effect.

It makes sense, because it is the relatively unpredictable – or completely erratic – situations that offer the most useful opportunities to learn something about the world around us. Just consider social norms of behaviour – they tend to follow some regular rules, but with a lot of variation, and curiosity about those irregularities will make it easier to navigate similar situations in the future.

In July this year, Kidd reported finding the same patterns in rhesus macaque monkeys. “We seem to have this built-in mechanism that seeks out information with just the right amount of uncertainty so that we can integrate it with our existing understanding of the world,” she says.

As we grow up, humans are soon interested in much more than their immediate environment, of course –we can become deeply fascinated by abstract topics, such as mathematics or philosophy. Often, the objects of our curiosity may have little immediate use in our lives. “We spend a lot of time getting information without knowing its value,” says Gottlieb. In many cases, the best way to measure this interest is by simply asking people how curious they feel to learn a particular fact or subject.

According to one influential idea, we are particularly curious when we face an “information gap” – some unsolved mystery or unanswered question. In much the same way that those visual scenes for children needed to have the Goldilocks level of predictability and uncertainty to grab their attention, the size of the information gap matters. If it is too big, the question or topic feels unmanageable and daunting; too small, and it feels like irrelevant minutiae best ignored. We are most curious about stuff that falls somewhere between the two – something that is surprising and useful, but not wholly unfamiliar.

Finding that balance will be crucial for learners and their teachers. Numerous studies have shown that the more curious people feel about getting the answer to a trivia question, the better they remember the fact. And by asking people to report their own curiosity while they viewed different facts in a brain scanner, Matthias Gruber at Cardiff University, UK, has discovered the reasons why this is so.

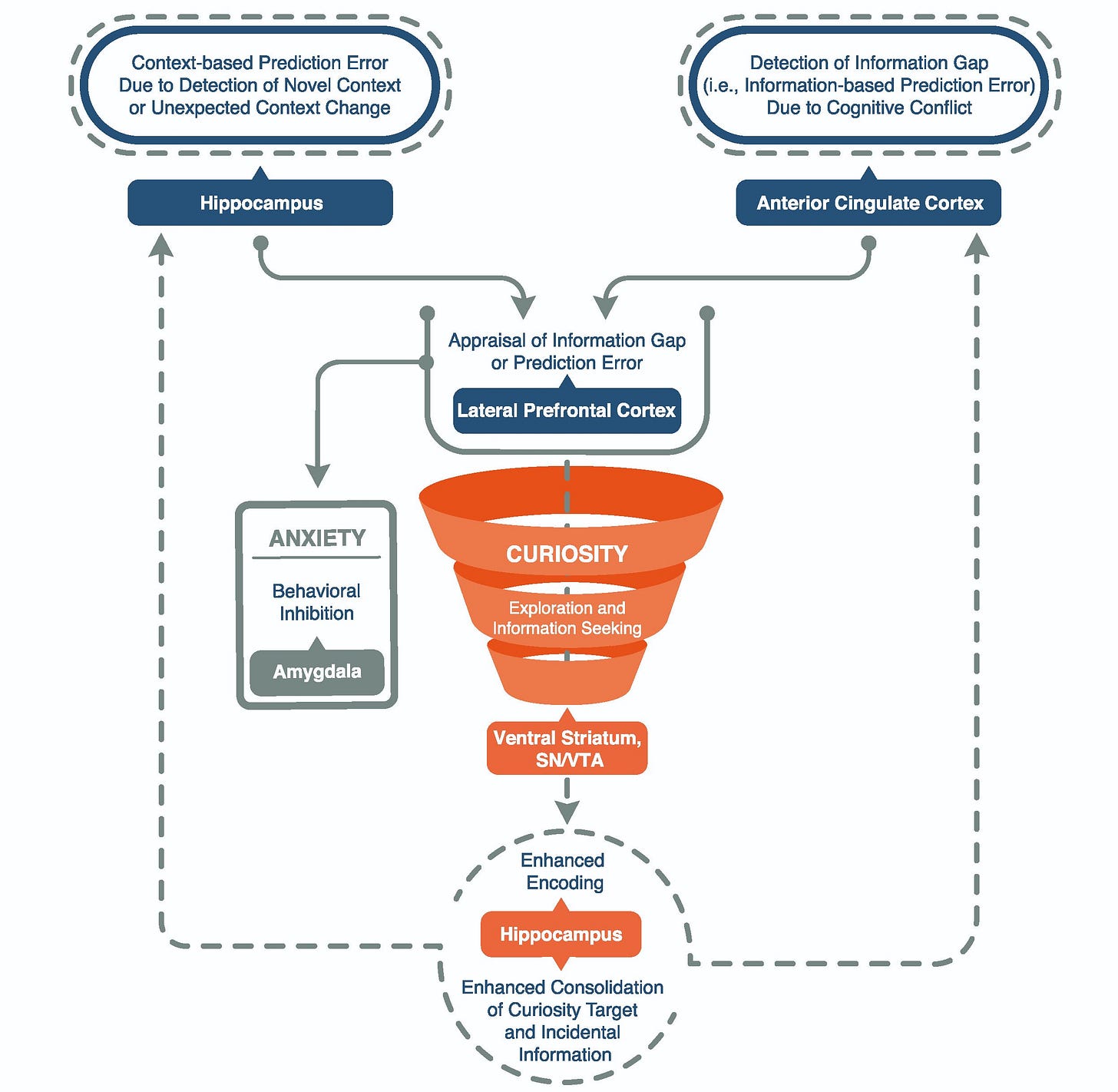

In Gruber’s model, curiosity begins with some kind of uncertainty or information gap that activates the hippocampus –which, along with its role in memory, also detects novel stimuli – and the anterior cingulate cortex, which monitors informational mismatches in the brain. The brain then appraises how rewarding it will be to fill in the hole in its knowledge, which shows up as activity in the prefrontal cortex.

This last step is where the most variation between people is seen. “The same stimuli could elicit different degrees of curiosity, no curiosity at all or even anxiety about the uncertainty or novelty,” says Gruber.

If that appraisal is positive, we enter a state of curiosity that activates the dopaminergic circuit in the brain related to reward processing and memory. This also tags information encountered while curious as especially salient, which helps forms stronger memories. “Curiosity warms up these circuits and the hippocampus to prepare the brain to learn and create long-term memories,” says Gruber.

His research has found that these benefits spill over to other incidental information presented at the same time as the objects of their fascination. If participants were shown a trivia fact that had aroused their curiosity, alongside a photo of a face, for example, they were much more likely to recognise that person later on– even though it had nothing to do with the information that had first sparked their interest.

Five dimensions of curiosity

Then there is curiosity’s capacity to lead us down dark and depressing avenues –something that may be particularly harmful when trying to cope with difficult situations like the covid-19 pandemic.

Such complexities have led some researchers to argue for a more nuanced approach that considers the many ways that Hobbes’s “lust of the mind” can be expressed. Todd Kashdan, a psychologist at George Mason University in Virginia, has led the way by developing a model that considers five “dimensions” that shape our curiosity.

One of these, “deprivation sensitivity”, reflects our tendency to experience the mental itch when we encounter information gaps – the intense need to know an answer that leads us to solve problems and resolve mysteries. A second, “joyous exploration”, describes a wider-ranging interest, experienced as a genuine pleasure in learning about new subjects and thinking about things in depth.

Together, these two dimensions cover the epistemic curiosity that was traditionally the topic of psychological study. But Kashdan goes further. He considers “stress tolerance”, for instance, which is your ability “to accept the anxiety that is a natural part of confronting the new”, he says. This takes into account the fact that some people’s anxiety can lead them to shy away from the unknown, while others manage those feelings more successfully. “Often, people would like to explore something, but they don’t feel able to handle what that involves”, he says.

Related to this, Kashdan also cites “thrill-seeking” as a factor –whether “you would take serious health, financial, legal or social risks to acquire novel experiences”, he says. Someone who leans strongly this way would take any opportunity to do something new. The final dimension, “social curiosity”, concerns our willingness to learn from other people.

There now seems little doubt that the distinction between the first two factors is crucial in understanding curiosity’s true effects, for good and bad. In studies on curiosity and creativity, “joyous exploration” is more than twice as strongly correlated with creativity than “deprivation sensitivity”.

people who scored high on deprivation sensitivity who were more likely to fall for fake news and bullshit, while those high in joyous exploration didn’t seem prone to this.

Kashdan’s own research, published in 2020, shows that these dimensions can determine different outcomes in the workplace. Higher levels of joyous exploration and stress tolerance offered the best predictors of innovation at work, while a combination of high stress tolerance and high social curiosity led to the greatest overall workplace engagement and job satisfaction. He has also demonstrated that people generally tend to fall into four distinct subgroups, depending on their scores on the different dimensions.

“Much of this is temperamental,” says Kashdan. But that doesn’t mean you can’t try to nurture your curiosity in general – and joyous exploration in particular. Given that you are reading this magazine, you are already doing one of the most important things: opening your self up to new ideas that may spur you to find out more and more. Keep it up, as you broaden and build your capacity for curiosity. You can try new foods, listen to new music, check out a new TV show or podcast or visit a new city. Talk to people and ask them questions.

Along the way, you can use these opportunities to build tolerance for the uncertainty that is inherently tied up with exploring unfamiliar topics and trying new experiences. You might also try to get over any embarrassment at showing your ignorance in front of people, suggests Kidd. “You need to develop tolerance for not knowing stuff, especially in a social domain, and become comfortable saying ‘I don’t understand what you mean’ or ‘I don’t know how to do that’.”

If you are feeling anxious about the unknown, and shying away from it as a result, you could try to reframe those feelings as excitement and view your ignorance as an opportunity for growth. As Gruber points out, a positive appraisal can make a big difference for the curiosity someone feels and expresses.

As long as you are mindful of the potential for distraction– and ensure that you feed your curiosity with intellectually nutritious sources of stimulation, rather than clickbait and fake news – these steps should lead you to greater happiness and fulfilment. “The good life, as most philosophers have argued, starts with knowing yourself and understanding your values and propensities, what makes you you,” says Kashdan. “Curiosity opens up pathways that can really lead you to understand your primary sources of meaning and purpose in life.”

Provocation

Strangers are fond of asking couples how they met. Far less often do people ask, “how did you stay together for 15 years?” Movies capture super hero origin stories but rarely do they attend to what keeps their lives interesting after decades of fighting crime. Take as much interest in longevity as beginnings. Show as much intrigue in older adults as youth - asking questions, seeking stories, and pursuing connections. In case you missed it, the last issue of Provoked dispels the myth that curiosity disappears with age.

If you enjoyed this newsletter, please leave a ❤️. Even better, share it with friends. If you’re reading my new book, The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively, send me thoughts, questions, & beefs. I love hearing from readers.

………………………………………………………………………………..

Extra Curiosities

The WATCH/LISTEN - Hanging out with Rick Hanson and his son Forrest Hanson. I only hope I get along this well with my kid. Lots of laughter, love, and trash talking in this hour.