If you seek connection, join the wise, playful, compassionate, non-judgmental Provoked community - and get access to monthly calls and 200 archived posts.

As a psychologist, I regularly think about the ignored gray zone between the so-called “sick” and “well.” I’ve written about the problem of people self-diagnosing themselves with psychological disorders when in fact, they might just be surrounded by difficult people in difficult situations [here]. There is such a strong desire to simplify things by slapping on mental health labels.

You have social anxiety disorder - ignore the assholes surrounding you at work.

You have dysthymic disorder - ignore the sleep deprivation and sense of despair from taking care of two rambunctious, energy-absorbing kids with an emotionally disconnected partner.

Categories help us organize things, making it easier to understand and communicate. However, when we categorize people into bins, this produces artificial limits on people by creating divisions between those who are “sick” and “well.” For categories to be useful, the cut-offs must be clear and relate to what is happening in the real world.

To understand the problems with psychological diagnoses, let’s slip into a recent social trend - the trivialization of trauma.

Flippant Claims of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Your computer crashes right before you saved an important document.

Blanking on questions during an interview and not getting a job.

Being in a relationship with a highly narcissistic partner.

Working in a (“toxic”) work environment where there are excessive demands, manipulative colleagues, and unprovoked arguments.

Misunderstanding a text that causes confusion and problems.

While these moments can be anxiety-provoking, depressing, or infuriating, equating them with PTSD, or Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, does a disservice to those who truly suffer from this condition. PTSD affects hundreds of thousands of people each year, including sexual abuse survivors and military veterans. It's not just about feeling alienated or discombobulated. Here’s some clear thoughts on the topic by my graduate school mentor/friend:

If you want to ignore Chris and prefer to read the details, here is the PTSD definition in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

To have PTSD , you must have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event, such as actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence. The symptoms, which include intrusive memories, avoidance, negative changes in thinking and mood, and heightened reactions, must persist for more than a month and cause significant distress or impairment in daily life.

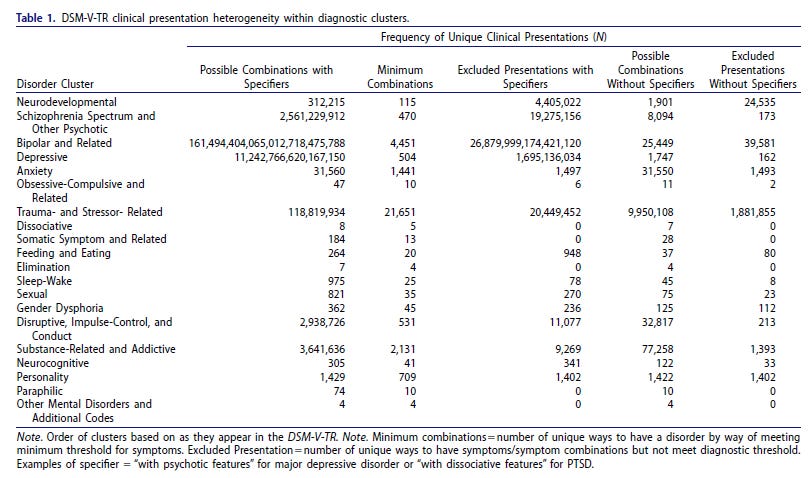

The challenge of determining whether PTSD is present is highlighted by the staggering number of symptom combinations possible: There are 636,120 unique ways to have PTSD! With this many combinations, there is no reason to add even more ways for a person to quality for PTSD.

Recently, my 17-year-old daughter experienced a distressing incident at the veterinary clinic where she works. The clinic takes in dogs abandoned by owners, and some of these dogs can be quite aggressive. On one occasion, an employee was walking one of these dogs when it suddenly bit her face. The attack was severe, and the dog did not let go. Her face bled heavily, and the cartilage in her nose was torn, necessitating plastic surgery. Witnessing the aftermath left my daughter visibly shaken. She struggled to recount the event without becoming emotional and felt a lingering apprehension about returning to work.

Could my daughter finagle her way into a diagnosis of PTSD with the criteria above? Absolutely.

Could she then use this diagnosis to get out of responsibilities at school and work? Absolutely.

Does she have it? No.

What she does have is an autobiographical story where she witnessed something terrible, had a perfectly normal adverse reaction, and it lingered for a while. It would make an excellent opener to a college essay on why she remains undeterred in wanting to be a veterinarian .

The Many Ways of Having Disorders

The complexity of diagnosing mental health issues extends beyond PTSD. Prepare to be astonished by these staggering figures:

There are 10,130,814 unique ways to be diagnosed with a mental illness. When specifiers are considered, this number inflates to 161,494,415,307,782,025,621,351 (>161 septillion).

Consider that number for a another second. Septillions?!? There are way too many ways to be considered mentally ill. For details on our absurd current mental disorder model, check out a few more conditions below.

Something feels off, doesn't it? Can we wrap our heads around the idea that there are this many combinations of disorders? Or is there something else lurking beneath the surface?

Perhaps it's our modern world that's a bit under the weather, causing us to misdirect the chaos of the outside world inward, blaming our minds for the turmoil.

Maybe there's comfort in the scientific community's urge to label and categorize, driven by a well-meaning desire to ensure no one slips through the cracks without support.

And then there's Big Pharma, ever the opportunist, eager to turn each of these countless combinations into a new prescription and fresh revenue stream.

But let's pause for a moment. While the challenges of mental health can be daunting, sometimes that arrive with unexpected gifts. It's worth shedding light on a few benefits of the diverse thoughts and feelings that arise from psychopathology. Something I've been exploring for years...

For paid/premium subscribers, here's the latest scoop on why we should consider "silver linings" of living with psychopathology. Below, I also provide the date and time of our next Ask Me Anything call [watch the last one here].

I illustrate “silver linings” with three incredible biographical stories. Steal them for your next book…