The Genius Who Wasn’t Interesting Enough to Interview

The problem with discussions of what leads to creative accomplishments.

In case you missed it…

Provoked is for playful, intelligent, creative, and discerning readers. If you enjoy this article, support the mission (be a free subscriber or get premium benefits).

In 1970, a mathematician named Julia Robinson cracked a piece of Hilbert’s tenth problem, one of the most notorious unsolved puzzles in mathematics. She worked on it for decades. When her solution was confirmed, colleagues rushed to dissect “how she did it,” hungry for the origin story of brilliance.

You know what audiences and journalists want: Mental health problems. A difficult childhood. Something cinematic (link).

What they got instead, “I just kept thinking about it. Every day. For years.”

She didn’t abuse substances or experience a marital collapse. Just a woman who showed up to her desk, thought hard, and went home to stretch her hamstrings.

She is not alone and it’s a story worth repeating so that kids and adults alike can seek real heroism and know they might be able to do something similar if they put in the work (which a large minority do not).

-----

We claim to worship brilliance. But we want to be entertained, no different than a People magazine cover discussing a Marvel superhero who cheated on his spouse. We want the poet who overdosed. The CEO who abandoned her family. The actor who sobbed between takes. The work? It is often an inconsequential side dish of Kani salad.

When someone creates without visibly unraveling, we get suspicious. Their home life is intact and their therapist isn’t on speed dial, and they still make school lunches for little ones? Something doesn’t compute. We need a backstory to justify the output. So we don’t feel inferior. Yes, it’s usually about us.

No Wreckage, No Respect

Picture a stand-up comic who destroys onstage, then goes home to tuck in his kids and floss. Where’s the bourbon? The divorce papers? The 3 AM existential spiral?

We’re wired to distrust calm excellence. Wholeness looks like a con.

And that leads to the sick irony: greatness in any craft usually requires showing up sober, shutting up when necessary, and iterating without combusting.

We don’t cheer for that. We want Hemingway bleeding into his typewriter.

When someone creates astonishing work without theatrics, we shrug and call them boring.

Boring Is the New Dangerous

Boring is terrifying (sort of).

Boring is discipline in a culture that fetishizes impulse. Boring is restraint when everyone else is live-streaming their meltdown to a million followers.

You know what’s boring?

Predictable entitlement-infused emails to hired help, such as digital assistants and home cleaners. Spending a decade in the fetal position because you think therapy will kill your edge.

Boring is subversive now. The boring person says I know who I am, and I will not pretend that the work is synonymous with my being.

This often freaks people out more than public meltdowns.

Why The Myths Persevere

Most of us WANT the myth to be true. Because if genius requires addiction and social annihilation, we get to opt out guilt-free. “Sure, I could have been great… but I wasn’t willing to risk it all and fuck up enough.”

It’s a get-out-of-ambition-free card (mention me in a footnote if you turn this into a board game).

We fixate on Van Gogh’s ear. Sylvia Plath’s oven. Their unraveling, ironically, makes them safe. It renders greatness inaccessible, which means our failure to achieve exceptional outcomes isn’t our fault.

After all, if greatness doesn’t require collapse, then what’s your excuse?

Normal, healthy human beings who do great things offer a testament that yes, you can do it. You can take on an audacious goal. And then the pressure lands back on daily habits. And daily habits are uninteresting adulting.

Give Me the Genius Who Does the Dishes

I hope you’re with me. I want to meet the chess grandmaster who coaches Little League.

Eccentricity is easy. Anyone can flame out by giving in to those impulses that chatter away in that big brain. In contrast, building something that lasts without blowing up your life every three years for material? That takes work.

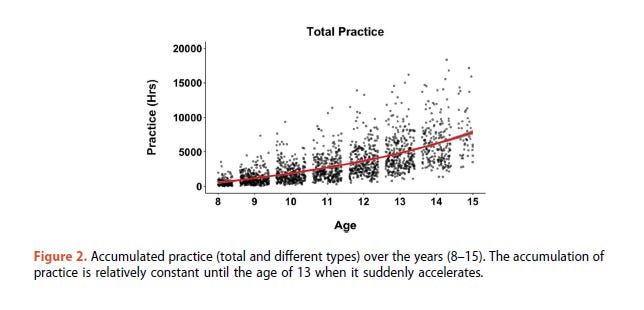

True mastery is boring. Repetitive. Obsessively calm. When you study young elite athletes, what you find is that as they move from overinvolved parents to autonomy, they show an acceleration in their desire to practice. And those small experiments and drills have a snowball effect.

Julia Robinson made headlines because she was stable, worked at problems relentlessly, and her proof changed mathematics (all three mattered - link). Meanwhile, we’re still talking about the actor/musician/scientist with the most outrageous statement. Priorities, people.

So What Do We Celebrate?

We need new icons. Celebrate the boring people who create beautiful things.

When someone’s brilliance doesn’t come with a backstory soaked in blood and bourbon? Respect it more.

You can make something great and still go home early.

And somehow, against all our cultural programming, that turns out to be enough.

🔒 For the Curious

Want more left-of-center topics in your inbox? Subscribe. Share this with someone who still thinks tortured is a prerequisite for awesomeness. Or don’t. I’ll be here either way, probably doing something boring like revising this with a protein smoothie that’s gone warm.

Comment - I will respond here and in the chat room and virtual calls.

Todd B. Kashdan is the author of several books including The Upside of Your Dark Side (Penguin) and The Art of Insubordination: How to Dissent and Defy Effectively (Avery/Penguin) and Professor of Psychology and Founder of The Well-Being Laboratory at George Mason University.

“I just kept thinking about it. Every day. For years.”

Dang--what a recipe for success. I'm going to use this quote when I talk with students.

I really enjoy this line of reasoning. Thanks Todd. It makes me think of Scott Barry Kaufman’s concept of performative vulnerability, which, at least in my interpretation, is partly driven by media logic.