Tectonic shifts are stirring in society. People are questioning norms and beliefs inherited from prior generations. Companies and employees are no longer loyal to one another, as the average adult holds 12 jobs in their lifetime. A large proportion of society no longer lives near family and friends, which accounts for declines in well-being. Then there is the commodification of social media. The destabilization of the New York Stock Exchange. The systematic decline in religious beliefs. Cultural debates span the topics of education, health care, money, race and gender, the criminal justice system, how to date and mate, attitudes toward the natural world, and work-life balance. There is an urgent need for tools and strategies for thinking critically, not passively, about the variety of ways life can be lived, not for the sake of diverse thought but for an improvement in better decision-making and creative solutions.

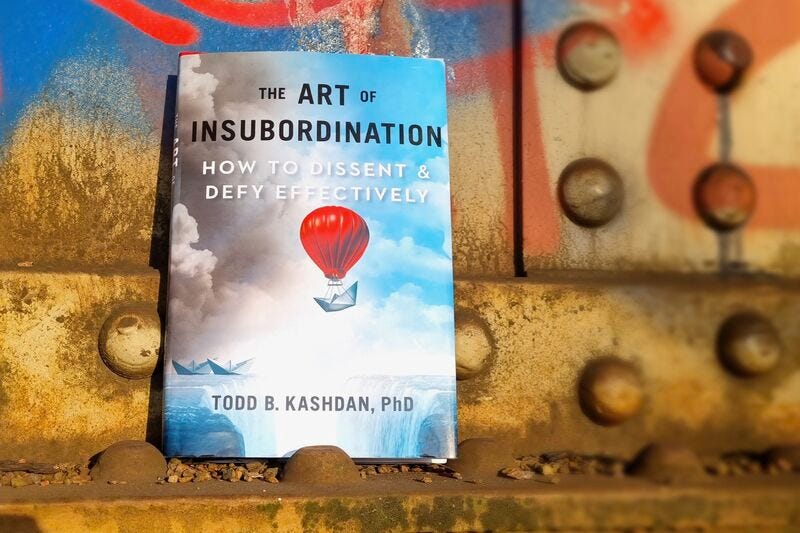

It remains unclear whether to reinforce existing systems or to replace them with something better. This question led me to explore what science has to say about equipping people with knowledge and skills to construct better lives for themselves and a more utopian world in the face of immense, seismic shifts. The Art of Insubordination is my answer. The book is an operator’s manual for optimizing groups and improving society. In it I arrived at the conclusion that reasonable dissent is our best protection against conformity mistakes. To prevent the erection of unhealthy systems and leaders, we need principled people who are willing to be different, to deviate, and to dissent. Even more to the point, for principled dissenters to stand a chance at being successful, the rest of us must be intellectually humble and curious enough to give new ideas and perspectives a fair hearing.

I am not the first person to write a book on how to challenge flawed mainstream thinking or how to disagree in a productive manner in hopes of changing minds. I believe, however, that prior efforts to understand the positive function of constructive dissent merely skimmed the surface of existing knowledge. Upon reading 60 years of research on minority influence, I decided to write a handbook on how to engage in persuasive dissent when conventional thinkers are wrong.

Transcending Traditional Views of Dissenters

Here’s the problem: There are steep up-front costs for permitting and embracing dissent. A lack of consensus is an inefficiency — groups have to pause, listen, and decide how to respond instead of plowing away at important tasks. It is easier and faster to make decisions and complete goals when there is consensus and harmony.

We all want to be liked, preferring praise over contempt. Members who fail to stay between the lines of acceptable conduct are likely to be judged harshly, if not become a target of criticism, scorn, derision, threats, and ostracism. Take Dorian Abbot, whose insistence upon an alternative metric for supporting diversity in the university system produced unforeseen social persecution. His values are transparent on a university website: “I practice fair admissions: I select students and postdocs on the basis of scientific ability and promise, and I do not discriminate against any applicant based on anything else.” Invited lectures on his area of expertise, climate change, were rescinded, not because of his scientific contributions but because he does not support affirmative action in student recruitment. Then there is Elon Musk, who in taking over the helm as the owner of Twitter had his team scroll through internal messages on Slack, emails, and social media to find employees who criticized him or the company. Upon rounding up the dissenters, Musk fired them. Sometimes these firings occurred in a publicly shaming social media post. Every day offers fresh incidents.

Traditionally, a dark picture is painted of citizens perceived to be nonconformist, contrarian, rebellious, dissenting, insubordinate, or just plain different. Only if successful will they then be celebrated with the likes of heroes known by one-word names — Mandela, Copernicus, Gandhi, Tubman, Tesla, Darwin, and Churchill.

Here’s the solution: Scientific research offers a more enlightened view of those who appear different, hold dissenting views, and deviate from the herd. If we care about innovation, and the health and longevity of groups that we identify strongly with, we must welcome people who are brave enough to question discriminatory norms. An assumed negative is in fact a positive and a necessity for social groups to reach their potential.

Even when we don’t like a principled rebel, when we are dubious of their position, when they are wrong, their mere presence improves the quality of thinking of those nearby. When exposed to perspectives unlike our own, we are mentally liberated. We search longer for information when trying to solve a problem, including information that both defends and runs counter to our position (i.e., a reduction in confirmation and conviction biases). We are more likely to consider multiple options, remaining flexible, before arriving at a conclusion. Being exposed to a dissenting view turns us into scientists trying to uncover the truth instead of politicians narrowing attention to what gains public approval. There is evidence that creativity increases in response to listening to an outspoken dissenter who resists the pressure to nod along with the herd. And by witnessing someone take an unpopular stand, audience members are less likely to remain silent in the future when a group embraces nonsense.

Welcoming the Dissenter

There are scientifically informed strategies for getting a dissenter to speak up when they possess unique information that can help a group become smarter and wiser.

It requires strategic messaging for an audience to hear new messages from unconventional sources (see Chapter 4, “Talk Persuasively”). For instance, there is a shortcut to winning the attention of an audience if you happen to be less agreeable or likable. Perhaps you have indispensable or special skills. When you possess unique knowledge about statistics or computers, you have a “glue role” in the organization. You answer questions, help people, collaborate, and amplify other people’s contributions. You don’t just do work well; the entire group is better with these rare, useful skills. You must carefully clarify what you did with these skills to benefit the group. Speak from the perspective of what the group has accomplished with you rather than how you are a star. Many people possess a unique portfolio of strengths, talents, and skills. Yours is one of many that adds to the group’s viability.

It also requires the recruitment of allies — those who champion ideas that run counter to traditional thinking (see Chapter 5, “Attract People Who’ve Got Your Back”). For instance, help people around you satisfy their two competing psychological needs in social situations: the need to fit in and the need to stand out. Offer verbal affirmations of how you care for, validate, and understand them. Describe their unique strengths that make them a linchpin.

It requires an ability to handle the social persecution that often emerges from resisting complacency and conformity pressures (see Chapter 6, “Build Mental Fortitude”). For instance, understand how you manage unwanted thoughts, emotions, memories, and bodily sensations. Discover the particular activities you engage in to distract yourself from or avoid contact with these feelings. With this knowledge, you can become more adept at finding alternative strategies so that you can harness negative emotions as motivational fuel.

It requires an audience willing to experiment with intellectual humility and curiosity (see Chapter 8, “Engage the Outrageous”). For instance, when entering a conversation with a motivation to learn instead of persuade, so-called opponents showcase greater open-mindedness. This also requires leaders who open the portal to difficult conversations — a launching pad to divergent thinking and creative bursts (see Chapter 9, “Extract Wisdom from ‘Weirdos’”).

And finally, it requires a cultural shift, where individuals are taught that the best group member is neither passive nor compliant but autonomous, disrupting unhelpful norms and voicing skepticism for the sake of progress (see Chapter 10, “Raising Insubordinate Kids”).

As may be obvious, the applications to the classroom and the faculty lounge are legion:

Create a culture where productive conflict is welcomed, with clearly expressed principles for how to engage.

Understand why people have a natural tendency to favor and justify the status quo and reduce this bias in the classroom, faculty meetings, and administration decisions.

Be open when nonconformists express their views. You don’t have to agree with them or change your mind. Just allowing them to speak and be part of the discussion improves the thought process of everyone present.

Build strong alliances by attending to the dual, opposing psychological needs of members in groups: the desire to fit in and stand out. Learn how to satisfy both of these needs in potential allies because you cannot change the status quo on your own.

Stay focused on the ways in which power compromises self-awareness. If your ideas are embraced, do your utmost to even the playing field for detractors. Treat those who support your views and those who oppose your views similarly. This will be hard as you are pulled to engage in favoritism toward friends and denigration of foes.

Cultivate curiosity. When you encounter an opposing or unfamiliar viewpoint, begin from a place of open skepticism about your own beliefs. Redirect your attention to what others offer. Talk less and ask more.

Be vigilant. Culture building takes time, and once you see progress, you must stay alert to prevent backsliding. You can build groups in which disinterested inquiry and the ability to get information about what it’s like to navigate the world in someone else’s skin become entrenched.

Moving Toward an Aspirational Society

We don’t gain wisdom by shopping for friends who look, think, and act like us. We must seek exposure to people who make us think hard about whether there are glaring blind spots in our belief system. Our ability to grow as a person is enhanced by the presence of dissent. The speed of cultural evolution is faster with the allowance of dissent. Higher education would do well to ensure that its teachers, deans, and presidents not only comprehend these truths but cultivate them where they have responsibilities.

There is a better world within reach, where we support principled dissent and productive conflict instead of squelching it. Where we are part of organizations that share and debate ideas, instead of the far too common situation where self-censorship and silence reign. We need to be sufficiently curious about what is possible, courageous enough to take constructive action, and intelligent enough to know when and how.

Dissenting and defying practices that are stagnant, ineffective, and/or dangerous are too important for hunches and intuition. The Art of Insubordination offers the path forward for increased personal well-being, healthier groups, and a better-functioning society. Apply scientifically informed strategies to produce messages that change minds, build mighty alliances, manage the discomfort when trying to rebel, and unlock the benefits of being a group of diverse people. It won’t be easy being a rebel or championing one, but it is the mechanism for designing classrooms, disciplines, teams, organizations, and a world with more courage, creativity, justice, and truth.

The best way to support me is by sharing this work widely. And click the free ❤️ button.

I love hearing from readers. Email me (todd[at]toddkashdan.com).

NOTE: This is reprinted from Heterodox Academy (with a stirring educational mission).

And If You Missed the Last Issue…..

At least six fears prevent people from capitalizing on their unique knowledge and strengths in groups. Know them. Reduce them. Click below for the details.